The following was published in the 14th Ave. Church of Christ bulletin on 4 February 2018.

Today we consider three hospitality tales in the Hebrew Scriptures. Our first tale takes place in Genesis 19, where righteous Lot “entertains angels unawares,” to use the the Hebrew writer’s phrase. Lot insists that the strangers spend the night in his home rather than in the town square, and we soon discover why. The men of Sodom want to take advantage of them because they are foreigners.

Lot enrages the men of Sodom by refusing to turn over his house guests. The Sodomites accuse Lot of being an uppity foreigner and tell him that he will suffer a fate worse than a foreigner at their hands.

The Lord had already decided to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah before this episode, but this is the icing on the cake. Lot has shown the strangers mercy and hospitality, so the Lord shows him mercy. The cruel Sodomites, on the other hand, see an opportunity to have their way with some hapless foreigners, so the angels destroy them.

Lot’s daughters, having fled into the hills with their father, realize that he is in trouble: he has no heir, no wife to give him an heir, and no prospects for getting a wife. Their “creative” solution is to get their father drunk and make heirs for him themselves. Thus they bear Lot two son: Moab and Ben-ammi, the fathers of the Moabites and the Ammonites. (By the way, note the irony here: Lot’s daughters have taken advantage of him in the same way the men of Sodom sought to take advantage of the angels.)

Our second tale takes place several centuries later. Abraham’s descendants are sojourning out of Egypt toward the promised land, and they come upon the lands of the Moabites and the Ammonites, Lot’s descendants. Far from welcoming their kin hospitably as Lot welcomed the angels, Moab and Ammon fear Israel and seek to destroy them and curse them (Num 21-22).

This complete lack of hospitality is revisited upon Moab and Ammon after Israel settles in the promised land. The Law commands, “No Ammonite or Moabite or any of their descendants may enter the assembly of the Lord, not even in the tenth generation. For they did not come to meet you with bread and water on your way when you came out of Egypt, and they hired Balaam son of Beor from Pethor in Aram Naharaim to pronounce a curse on you.” (Dtr 23.3-4).

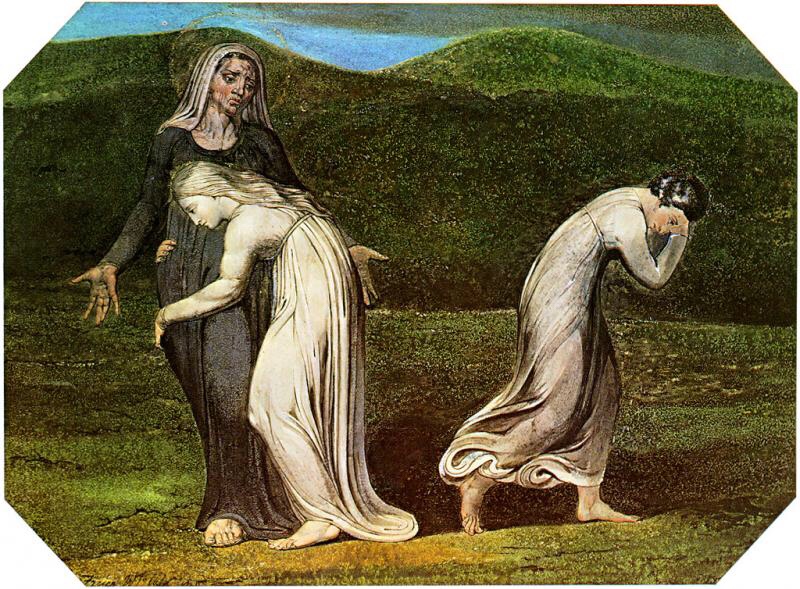

The third tale takes place generations after the Exodus, during the time of the judges. An Israelite, Elimelech, sojourns to the land of Moab with his wife and sons. Elimelech dies, leaving his family to fend as foreigners in Moab. The sons marry Moabite women, then also die, leaving behind three widows: Naomi, Orpah, and Ruth. Naomi, unable to live as both a widow and a foreigner, turns back to Israel. She tells her daughters-in-law to return to their fathers, because they will be both widows and foreigners if they travel with Naomi to Israel.

Ruth decides to stick with her mother-in-law and to take the God of Israel as her God. She predictably faces starvation in Israel. The Law compelled Israel to care for widows and foreigners, but each man in Israel was a law unto himself in those days.

Naomi’s kinsman, Boaz, shows Ruth incredible care. He goes above and beyond the Law’s requirements, allowing Ruth to drink from the workers’ water, dine with him, and glean more than her due (Ruth 2.9, 14, 15-16; cf. Lev 23.22; Dtr 24.19). Ruth recognizes his great favor, exclaiming, “Why have I found favor in your eyes, that you should take notice of me, since I am a foreigner?” (Ruth 2.10). Beyond all this, Boaz marries Ruth–again, above and beyond the requirement of the Law.

These three stories about Lot and his descendants give us three angles on the plight of the foreigner and what it means to be hospitable. Ruth shows us how dire the plight of the foreigner can be, uprooted, a stranger. The Moabites show us that our fear of the foreigner isn’t an excuse for hatefulness. Lot shows us that hospitality is a saving grace that bears its own reward; Lot thought that he was saving some strangers, but they ended up saving him!

Of course, we must remember where this all heads: Ruth is the great-grandmother of King David, whose lineage gives birth to Jesus of Nazareth. This same Jesus commands us, His followers, to live up to the Law like Boaz did: to consider the plight of the widow, the orphan, and the foreigner; to protect them and provide for them; and to include them rather than holding them at arm’s length. The alternative is to be like the Sodomites or the Moabites.

“Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares” (Heb 13.2).

Header image: “Naomi Entreating Ruth and Orpah to Return to the Land of Moab,” William Blake (1795)